One Sentence Mom

She was a prized candidate for THE prize

When I heard of this year’s Nobel Prize for Writing winner, László Krasznahorkai, I thought of my mother. Why? She was not a literary scholar. She was not a writer. She was not an aggressive reader save for Ladies Home Journal, romance novels or Zane Gray. So why the comparison? Where does she fit in this literary puzzle?

It’s because I tried to read something by Krasznahorkai, the novelist and screenwriter, and I banged into a brick wall. Why? Because his writing is characterized by long sentences, few line breaks and few paragraphs. It’s not my style, likely because I don’t appreciate or understand it. And I could not give it the attention it deserved.

A cult figure in world literature, Krasznahorkai is known for sprawling, hypnotic prose and bleak humor.

Born in 1954 in the small Hungarian town of Gyula to a Jewish family that survived the Holocaust and concealed its identity, Krasznahorkai has spent decades chronicling moral disintegration and spiritual endurance.

In his novel, Satantango, each chapter is a single paragraph with no line breaks. A single paragraph per chapter with no line breaks.

His most recent novel to appear in English, Herscht 07769, is a single sentence that unfolds over 400 pages. One book, single sentence. I struggled to read two pages because I could not stay focused. I’m a traditionalist grammarian, one who appreciates simple sentences . . . subject, object, predicate, PERIOD. That’s the way I was taught. That’s why I love Hemingway. That’s the way I write (my style, not Hemingway).

How does my 90-year-old mother come into this?

Some years ago, I gave her a blank diary with a question on each page.

· Who was your first girlfriend? First boyfriend? First school?

· What was your favorite toy? Favorite dress?

· How did you meet Dad? Why did you marry him? etc., etc.

My mother was not at a loss for words. She wrote, and wrote, filling every page. The problem?

She, like Krasznahorkai, never punctuated a thing. All the answers were one endless sentence. She took some breaks. Every now and again, she would insert, “Would you believe I love you?” And throw in some love bots . . . . XOXOXOXO to keep me on my toes.

The answers are treasures, but they were not good enough. What I should have done was video her. She would have soon forgotten that the video was running, and we would have seen her animation, heard her words, in her home, comfortable in her space. And the one sentence a-punctuated tome would not have come into play.

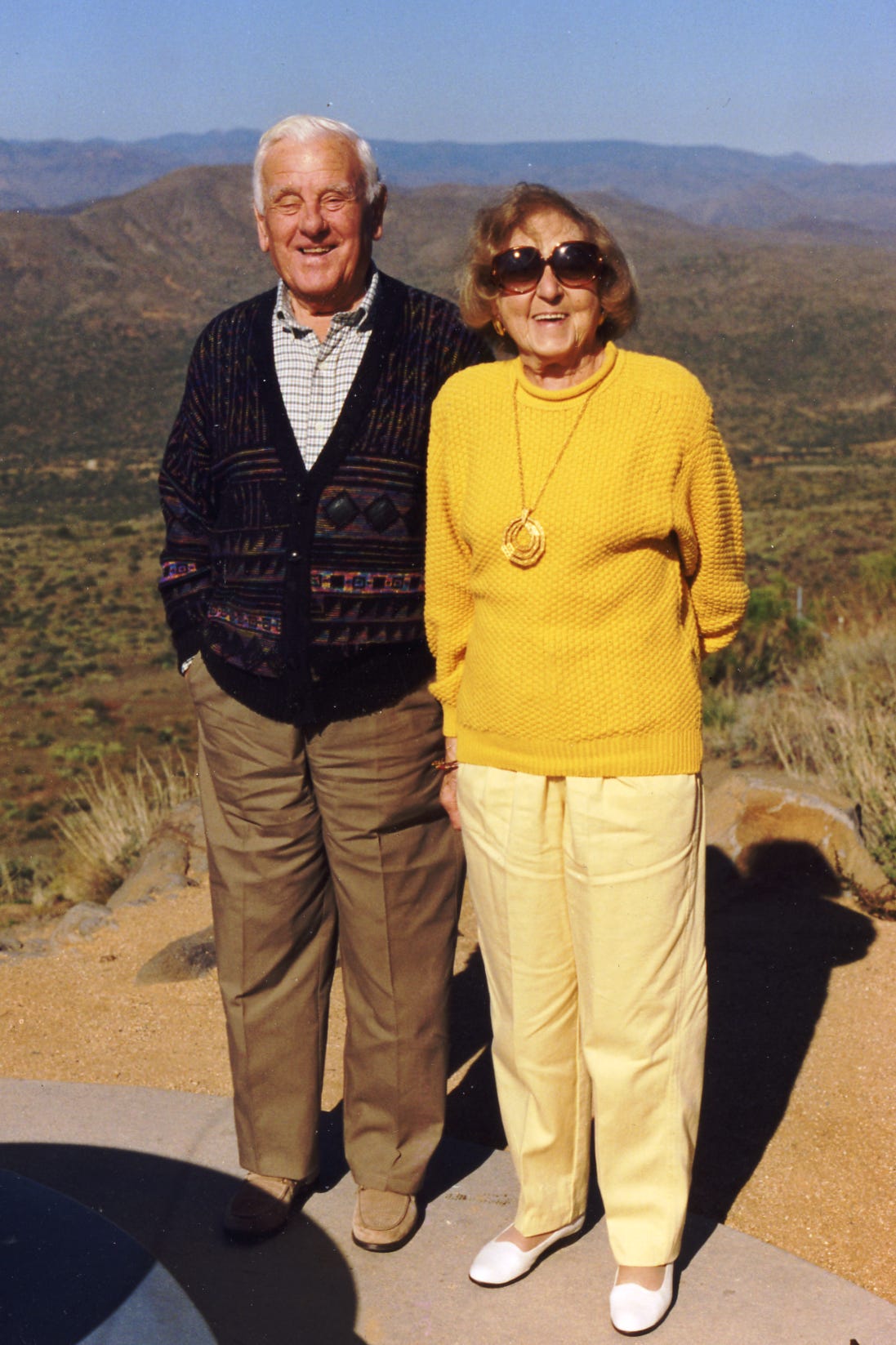

So Peter and I decided to do something akin to my idea of videotaping. We sat side by side in front of the camera answering questions about our youth, our family, our parents and our adventures. My nephew, a videographer, inserted the old pictures in places to match our discussion.

He put together a cinematic marvel, following which we had a huge family gathering, served pasta and meatballs, and staged a Hollywood opening minus the search lights, red carpet and paparazzi. The meatballs were enough.

It was a fabulous and memorable success. I’ve digitized copies and sent them to all.

We should have videoed you, Mom. Then the one-sentence paragraphs would not have made a difference.

Ya could a been a Nobel candidate.

Would you believe we love you? XOXOXOXOX

Ó 2025

Great tale, Ed!

I remember your mom. You’re fortunate to have had her with you for a good part of your lives. Nice memories.