Lost In Translation by Gail Romanovich

Immigrants modify the laguage to assimilate

It was at my Grandma Ida’s dining room table that our family shared not just food but also stories.

My father and his sisters, Ophalia and Viola, shared some insights into the difficult relationship their Italian immigrant parents, aunts, uncles, and grandmothers had with the English language.

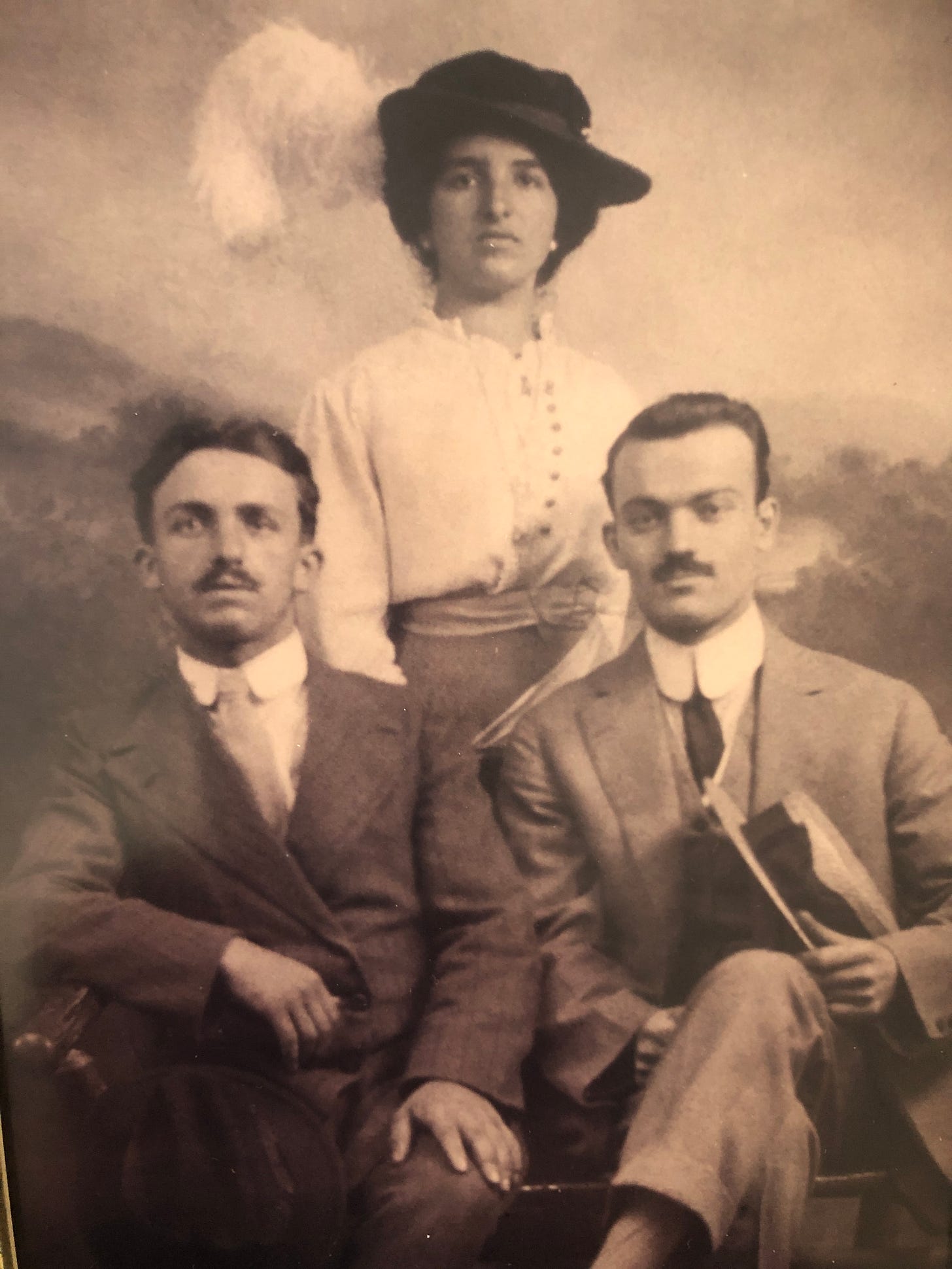

Grandma Ida came to America with her brother, Alfredo, in July 1914, at the outbreak of WWI. They traveled from Naples to Boston on the S.S. Canopic, a passenger liner of the White Star Line. Because they arrived a day earlier than expected, no one was at the port to greet them. Despite not knowing any English, they managed to take the train and navigate their way to America Street on Federal Hill in Providence, RI.

The purpose of this journey was for my grandmother to wed my grandfather, Giovanni, in an arranged marriage. He had been living in Providence since 1899, having arrived at the age of fourteen with his mother and sisters. He received his education there and had established his life in the community.

Grandma learned to speak a unique and endearing version of English. At one of the city’s finest department stores, she approached the hosiery counter and confidently asked the clerk for a pair of stockings size “half past nine.” The clerk blinked, unsure whether to check the time or the inventory. During the depression, Grandma stretched every dollar. She often bought day-old bread, which she called “one day stale.”

Some English words were not easy for her to pronounce. She was never able to say my name—Gail—correctly. Instead, I became “Girl,” which she said with such warmth that I never minded.

When shopping for my grandfather’s birthday gift, she walked into Carl’s Dry Goods store on Federal Hill and told the shopkeeper that she wanted to buy a “shit” for her husband, leaving the man speechless.

A little at a time, Grandma’s mother, brothers, and sisters joined her and Alfredo in Providence. Language was often an issue when trying to make themselves understood. Grandma’s brother Luigi met an attractive young woman at a dance at Rhodes On The Pawtuxet, a ballroom in Warwick, Rhode Island. Awestruck by her beautiful, fair complexion, he attempted to pay her a compliment by saying that she had “nice white meat.” She repaid his compliment with a heavy-handed slap across the face.

When Great-grandmother Francesca arrived in America, she was puzzled by the many “SALE” signs in a department store. She turned to her daughters, asking, “Ma, perchè sale, tutto sale! Perchè si vende sale qui?” (But why salt, everywhere salt! Why are they selling salt here?) She found it strange that Americans seemed to sell groceries with clothing—until someone clarified that “sale” meant discounts, not seasoning.

The ice man-made deliveries every day, calling out “ICE” as he passed along the streets. To simplify the process, some customers would put a sign in a window facing the street showing how much ice was to be delivered. The sign was a large card in the shape of a square, resembling a block of ice. Each of the four sides displayed a price: 10¢, 15¢, 20¢, 25¢. Whatever amount was right-side-up indicated the cost of ice to be delivered that day.

Aunt Laura, Grandma’s sister, coming home from work, seeing no new ice delivery for their ice box, asked her mother in Italian if she had bought that day’s supply of ice. Apparently, the sign system wasn’t in practice at their house. Great-grandmother told Aunt Laura that no one came selling ice. Upon further inquiry, Aunt Laura discovered that her mother’s ears, which were trained only in Italian, didn’t recognize the iceman’s inquiry when calling “any ice.”

It sounded to her like “anisette,” so that’s what she thought the man was selling. Aunt Viola, after telling me some of these stories, queried how a country of immigrants managed to keep from “curdling the melting pot.”

I told her that I rather think the Italian ingredient has added spice to the blend in this pasticcio of a country.

Lovely 😊

In