I Took Art Metal and Woodworking Classes

. . . I loved George J. West Junior High School

The first day I attended West, I realized I was expected to behave responsibly in traveling from class to class. It was the first time I encountered kids from different schools, neighborhoods, and towns; some even bussed in from Scituate and Foster, far away, or so I thought.

I was close enough to walk to the school and far enough to give me a pause on those bitter-cold winter mornings when the frost burned my face and chapped my lips. I wore my favorite hat, the toque that, even though it was not ‘cool,’ was as warm and comforting as a good friend.

Toting a Kraft #8 lunch bag, I walked down Wealth, took a right onto Academy, passed the barber and the shoemaker, and then left up one of the many hills, usually Beaufort Street. Miss Carroll, my favorite teacher, lived there. Beautiful, kind, elegant, and engaging, she rose above classroom formality when she greeted me, smiling, “Hello, Edward. Good morning. How are you today?”

“Hi, Miss Carroll.”

An outstanding teacher, she was one of the many reasons I loved the school. I rarely missed a day and once received the perfect attendance award at the end-of-year ceremony.

GJW Junior High stood high in a residential neighborhood. It was named in honor of West, a lawyer born in Providence in 1852, a member of the school board, and active in public affairs. The school hunkered along Mt. Pleasant Avenue encompassing an entire block. Gymnasiums and recess areas were anchored on either end.

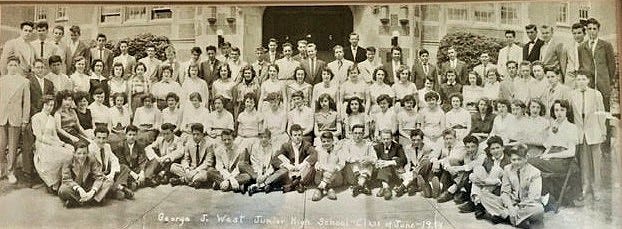

Elegant steps, memorialized in our 1954 graduation picture, led to the first floor that housed an auditorium with a stage and a balcony. Principal Cerilli, a taskmaster whom we feared and sometimes admired, proclaimed, “West is best.”

The student body was from different cultures that reflected neighborhood patterns; Italian Americans, Polish Americans, Irish Americans, etc.

Those bussed in were from the distant towns of Scituate and Foster. Because they returned to their buses after the last bell, not to be seen until the next morning, and certainly never in our neighborhoods, even on weekends, we hardly knew them.

Lockers lined wide wooden halls that smelled of varnish. My locker made me feel grown-up.

We started our day in homeroom joining a prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance broadcast from the central office through speakers next to which was hanging the U.S. flag.

I was a late bloomer, not one of the guys, and, realizing it early, I did my own thing as an early preppy (fag then, nerd now) surrounded by zoot suiters. I was conscientious and crowd-conscious and harbored only an imagination of mischief.

Academics were strong. I had tough, resolute teachers who prepared us for high school: Miss Flanagan, a stout, capable, idiosyncratic figure for Algebra, “Don’t forget to FACTOR.” Charming and clever Miss Carroll for English; testy Miss Turbitt for History; tall and distinguished Mr. Kirby for Art and Geometry; Miss Somers for Auditorium and so many others committed to their profession.

There were metal and wood shops, a gym for boys and one for girls. There was a cafeteria.

It was the first time I was exposed to woodworking and art metal.

Those classes met after lunch on the basement floor in adjacent rooms across from the cafeteria. After lunch was the best time for hands-on activity and the worst time for English or History with their soporific overtones floating over a baloney sandwich and Twinkies. It was easy to stay awake in Woodworking and Art Metal class. Sleep and you might lose a finger.

The smells of pizza and tapioca mixed with those of freshly cut wood, polished metal, and oil.

Wrought iron guards protected windows looked up to the tar-covered schoolyard where we played fistball. Low ceilings lent a level of security. The window guards were not there to keep us in. We wanted to be there. Rather they were there to keep shop-eager, tool-hoarders out. And, just maybe, to keep someone from stealing a potentially priceless work of student art. Wishful conceit.

Beams of sunlight full of dust and specks seeped through the grates.

Soft lights hung from metal wires. Machines were close to one another along the dull gray outside walls. An independent bandsaw stood in the middle of Mr. Spinney’s Woodworking room.

Mr. Lees taught Shop Metal; and Mr. Spinney Woodworking. Notwithstanding their shared goals of driving us to a finished product, they were different.

Lees was a robust, bulky guy with a relaxed, cheery-faced, enthusiastic manner, an ability to laugh, and a knapsack full of working-with-metal facts. He wore a grey smock that straddled to his thighs. His textured fingers were riddled with healed cuts and garnished with oil that sneaked under his fingernails.

Mr. Spinney, much more serious, was a partially paralyzed, lean fragile man who struggled walking so someone dropped him near the stairs to his basement realm. With crutches, he negotiated the stairs, bouncing down one at a time, then stopping, then bouncing. He shuffled into the room. His tremor, which I thought was not good for a woodworking teacher, was never a hindrance. I was transfixed when I watched him lumber to the band saw, flick it on, and with the care of a surgeon, maneuver a board to its center; perfect cut. He had all his thin fingers.

Spiteful little teacher jokes flew in the face of Mr. Spinney’s tremor and Mr. Lees’ paunch, but they were soon replaced by respect for what they knew, were able to teach, and how they did it safely; safety first.

They demanded respect for who they were and what they did. We became respectful. Lesson learned.

I loved the smells of milling metal, wood shavings, the belt of the metal polisher, and the whirring scream of the band saw.

In Art Metal, I made copper bookends with an emblem on each. Despite my uneven swirling polish, Dad loved them. “Neat, Edward.” I still have them; dull, uneven, tarnished surface and all. And I love them.

In Woodworking I made a three-level spice shelf that my mother appreciated despite its splotchy staining. She tucked it in a corner of the kitchen counter. Weathered by time in service, it became moldy, sticky, and stained, so it had long disappeared but not before ages in her kitchen and years of my boasting, “See that. I made it.”

After all these years I realize how important those classes were. They allowed me to socialize, lose the fear of conversing with the teachers, and walk around unconfined. I would like to say I learned lifetime skills of creating with my hands and fixing things, but I'm afraid not. But at least I produced two products. Then.

The girls had similar experiences. From classmate, Barbara:

“I took Home Economics/cooking or sewing classes. I did take Art Metal at least once, too. I remember a lot about what we sewed and how exciting it was to use an electric sewing machine, for instance. The cooking classes were eye-opening in as much as they opened my eyes to a version of "American" food that was unappealing. However, both classes were favorites of mine.”

And I learned:

To respect teachers in all disciplines

To respect the machines

To respect safety

To respect socializing in class

To respect learning practicum

To respect hands-on learning

To understand problem-solving

To understand planning and execution

To appreciate creativity

“I made those!”

Friend Tom relates his experience with a perceptive teacher.

In junior high, we were assigned to build a breadboard with handles carved with the band saw.

I showed my handles to the teacher. He looked, twirled them, turned to me, and said, “D___, do you know where the janitor‘s office is?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“Well, open the door nearby and you will see stairs leading to the boiler room. Go down, find the trash can, and throw these in.”

I was crushed, but he then helped me cut the perfect pair.

I have that breadboard today.

In a world increasingly dominated by digital experiences, I now realize that those classes provided crucial hands-on learning opportunities to work with real materials and develop tactile skills and 3-D awareness. How critical.

We need those classes today. More of them.

The classes taught us to find solutions, to be patient, and to think creatively.

I wish today that I pursued those skills. I understand how critical they are in playing a key role in our workforce.

I call those craftsmen for help, often.

And I watch. And I envy.

Yes Ed, I too attended George J West Junior High School (as it was called then), from 1973 till

1975. Yes, it was quite a shock, after spending six safe years at Robert F. Kennedy Elementary

on Nelson St. Exposed to tough kids from Olneyville and other tougher neighborhoods, I

had my first experiences with bullies. Made it though in spite of them and had many good teachers. In addition to wood shop with Mr. D'Ambra, who was teased unendingly, I also took

metal shop and printing, I still remember setting up the type in the huge printing presses.

Then I moved on to Mt. Pleasant and then graduated from URI where I met my wife.

Did not enjoy grade school but if it were not for all of those teachers I never would have gone to

URI. I still have both West and Mt. Pleasant yearbooks, I'm looking at them right now on my bookshelf!

I loved George West also. Ed, we were part of a great group in Room 310 with Miss Sherman . Beyond the academic opportunities and the super teachers, we had other opportunities. I was part of a group who made the morning announcements including the Pledge of Allegiance and the Lord's Prayer. I was a library assistant also and learned how to sew up a magazine to reinforce its cover and binding. Do you remember that Mr. Cerilli would broadcast the final innings of the World Series over the school's intercom each fall? Glee Club with Miss Collins, drama class with Miss Sommers, Home Ec and beginning work in Latin and Algebra with Miss Carroll and Miss Flannagan - so exciting. PE and having to change into a gym suit and sneakers was something new, and showering after class and before getting back to classes was always an adventure. What about Miss Flynn and our ninth grade project - a career book? Ed, what did you do yours on? I wanted to be a medical laboratory technician, or so I thought.The only career I knew I didn't want was teaching (My 14 year old self didn't like the look of those shoes our teachers wore), but teaching became my life's work, and I loved it. Thanks for jogging the memory chain.

.